DID THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE HAVE AN OFFICIAL LANGUAGE?

Official language, what does it mean? Is it the language spoken by all the people in a country? Is it the language preferred for government correspondence? Is it the language used among officials and when addressing the public? Or is it a language mandated by the state for communication with the public? First of all, it should be acknowledged that the concept of an official language is a 19th-century invention and is a consequence of nationalism. Moreover, it is not an innocent term and is associated with the notion of a nation-state. In fact, it has been used as a means of assimilating minorities by the majority.

A Person of Intelligence Can Learn!

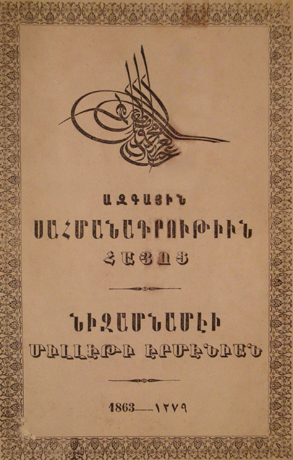

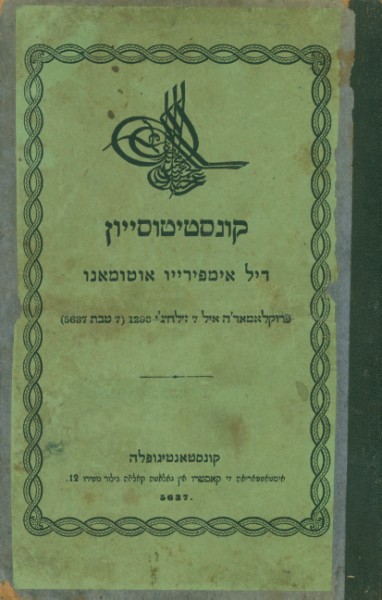

The matter entered our scope with the 1876 Constitution, the first Ottoman constitution. Article 18 of this constitution stipulated that knowledge of the official language of the state, Turkish, was a requirement for employment in state services. In response to Arab deputies who argued that this article was an obstacle for qualified individuals to become civil servants, the President of the Parliament, Ahmad Wafiq Pasha, replied, "A person of intelligence can learn Turkish within four years."

The initial version of this article included the phrase, "Each of the nations present in the Ottoman lands is free to learn and teach their own language." However, it was removed following the opposition of Eğinli Said Pasha, also known as English Said Pasha, who had studied engineering in England, stating that it would promote separatism. Nevertheless, after this, there was no harm to education and publications in local languages.

The influence of European currents during this period led to the attempt of forming an "Ottoman nation" comprising various elements within the state. Even if this claim is considered true, it did not achieve success. "Imperial subjects" and "nation" are contradictory concepts.

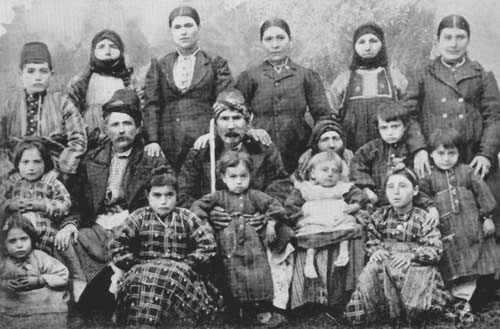

Therefore, discussing the official language of the Ottoman Empire is actually a futile effort. Empires do not have an official language; instead, various languages coexist within them and often influence each other. Some communities speak multiple languages. Even in the 19th century, the proportion of Turkish speakers was around 35-40%. In some regions, the Turkish-speaking population is more significant, while in others, such as the Aegean Islands, it is almost non-existent. The ruling class, including the dynasty, the military, and bureaucrats, spoke Turkish. Thus, Turkish has been the language of the dominant class in society since the Seljuks, in other words, the lingua franca.

In the Ottoman Empire, besides Turkish, official correspondence was conducted in various other languages such as Arabic, Persian, Greek, Armenian, Bulgarian, and others. The archives are filled with documents in these languages. Court records in Arab countries are in Arabic. Government yearbooks (Salnamas)) and the Official Gazette (Taqwem-i Waqaayi) were published in multiple languages, and laws were issued in several languages as well. Diplomatic correspondence was entirely in French, and the state even sent letters to its own ambassadors in this language. Official authorities accepted petitions in all languages.

The main principle was not to impose a cultural dominance but to ensure the functioning of affairs. Therefore, it was not a requirement for all officials to know Turkish; knowing the local language was considered sufficient. Some officials knew both Turkish and the local language. For example, the governor and qadis (Muslim judges) of Buda knew Hungarian and used it in official matters. If someone who didn't know Turkish needed to deal with a state office, no one would say, "First, learn Turkish!" Instead, a translator would be immediately provided. Islamic law grants this right to everyone. In fact, Hanafi jurist Imam Muhammad al-Shaybani stipulates the necessity of having two translators for official affairs, not just one.

The intention of the Qanun-i Esasi regarding the official language is clearly to ensure that officials have a common language. In other words, it aims to make Turkish a common language without prohibiting other languages, for the easy functioning of state affairs. This provision did not make Turkish the official language in today's sense. In practice, it was the same. For instance, one of the well-regarded grand viziers of the Qanun-i Esasi era, Hayreddin Pasha of Tunisia (1878-1879), was of Circassian origin and from Tunisia. He did not know Turkish and governed his country through an interpreter. However, even this is not as strange as King George I and II of England, who sat on the throne in the early 18th century, not knowing a single word of English.

Speak Turkish, Citizen!

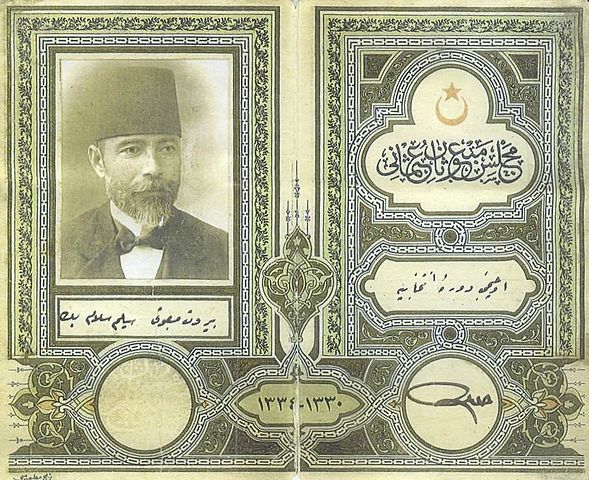

The members of the Committee of Union and Progress (Young Turks) used the provision in the Qanun-i Esasi mentioned above as a basis for their nationalist policies, going so far as to ban the use of languages other than Turkish and prohibit education in those languages. For instance, a transcript written in a provincial council with the seal of an Armenian member was rejected as it was deemed contrary to the principle of the official language stated in the constitution. The Albanian, Arab, and even Kurdish uprisings were fueled, in part, by this issue. The contemporary understanding of the official language is an inheritance from the Committee of Union and Progress. In 1910, while discussing the format for announcing laws in the parliament, there were heated debates over the official language. Non-Turkish members of the parliament unanimously agreed that laws should be explained to the public in their own languages. Hakkari Deputy Syed Taha Efendi stated, "Even though Kurdish is my mother tongue, I do not propose to declare it as the official language. However, the state should use necessary means and opportunities to explain the laws to the people."

In any country, the official language refers to the language used for official transactions between the state and individuals. A country may have multiple official languages, or it is also possible for a country not to have an official language. For example, France and Italy have only one official language, but minority languages are also officially protected. In Italy, Albanian, Catalan, Croatian, French, German, and Greek are recognized as regional official languages. In India, there are 35 official languages; in South Africa, 11; in Spain, 5; in Switzerland and Luxembourg, 4; in Belgium, Iraq, and Bosnia, 3; and in Cyprus, Ireland, Canada, the Philippines, and Finland, 2 official languages are recognized. On the other hand, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany do not have an official language.

In Turkey, despite the existence of multiple languages spoken, there is only one official language. The 1924 constitution and subsequent ones explicitly state that "The official language is Turkish." Based on this, the legacy inherited from the members of the Committee of Union and Progress was upheld, and campaigns like "Speak Turkish, Citizen!" were initiated, putting pressure on the ancient communities of the country, including non-Muslims. The language spoken by over 10% of the population for thousands of years was rejected as an "unknown language," and in the biographies of Kurdish deputies in the parliament records, their mother tongues were listed as "Farsi." During the Van earthquake, when an elderly woman cried out in Kurdish after her house collapsed, a high-ranking officer present there reprimanded her, saying, "Woman, first speak Turkish!" in order to uphold the constitution.

Settle the Accounts in the Evening!

In Article 39/4 of the Treaty of Lausanne, upon the proposal of Turkish delegates, any Turkish citizen was granted the opportunity to use their own language in private or commercial relations, religious and other publications, gatherings, and courts. However, the government interpreted this article as applicable only to non-Muslim (Greek, Armenian, and Jewish) citizens. On September 8, 1925, even in towns predominantly inhabited by Kurds, speaking Kurdish was prohibited, and those who defied this prohibition were penalized.

It is rumored that Mele Abdullah from Kozluk, in the 1940s when he went to Diyarbekir, was summoned to the municipality for speaking Kurdish and was fined 5 piastres for each word he spoke. He took out all the money he had in his pocket and put it on the table, saying, "Now I will speak in the market. Let the police come with me. We will settle the accounts in the evening."

In 1933, a crisis erupted when Naci Bey, an employee at the Wagons-Lits company, had a telephone conversation in Turkish, and the company's Italian manager, Gaetani Jannoni, warned him that the company's language was French. When Naci Bey objected, he was penalized, and this incident was reported in the newspapers. Members of the National Turkish Student Union attacked the Vagon-Lee company's agencies in Beyoğlu and Karaköy, and then proceeded to loot and vandalize the premises. The investigation concluded that it was a simple incident caused by young people getting carried away, similar to what happens in all civilized countries. President Mustafa Kemal requested that the police ensure the safety of the children involved, and they were all released. The company decided not to press charges. Jannoni, defending himself, stated that he had warned Naci Bey for speaking harshly to a customer and asked him to explain the situation, but Naci Bey responded by saying, "This is Turkey, I won't speak in another language." When he refused to pay the fine, Jannoni gave him a 15-day temporary leave, and he left wearing his hat. Jannoni was later dismissed from his job and brought to court, but the case was dropped due to the 10th Year Amnesty.

In the 1982 constitution, the phrase "The official language of the state is Turkish" was interpreted as meaning that languages other than Turkish could not be spoken in private life as well. In 1983, the "Law on Publications in Languages Other Than Turkish" was enacted. However, this law was abolished in 1991 when some members of parliament caused a crisis by taking their oaths in Kurdish.

Önceki Yazılar

-

FRIENDS OF ENGLAND ASSOCIATON24.04.2024

-

THE ASIA MINOR CATASTROPHE OF GREEKS17.04.2024

-

HOW DID WOMEN VEIL, AND THEN HOW WERE THEY UNVEILED…10.04.2024

-

HOW CAN HISTORY BE BELIEVED?3.04.2024

-

THE OFFICIAL MADHHAB OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE27.03.2024

-

WHO ORDERED THE PLUNDER OF ISTANBUL?20.03.2024

-

THE PLAYS BANNED BY SULTAN ABDULHAMID IN EUROPE13.03.2024

-

WHAT WAS THE MISTAKE OF THE UMAYYADS?6.03.2024

-

UNRAVELING THE UMAYYAD PERIOD: TRIUMPHS, TRAGEDIES, AND TRUTHS28.02.2024

-

OTTOMAN PENAL CODE AND HOMOSEXUALITY21.02.2024