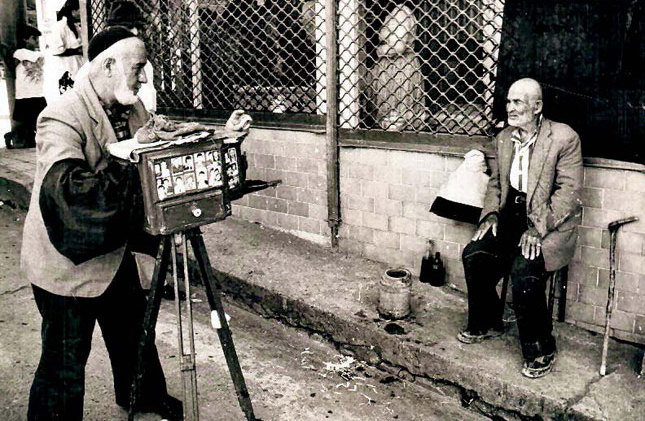

SMILE AND SAY 'CHEESE'

Tripod cameras attracted a great deal of attention when they were first introduced to Turkey in the 19th century in the final stages of the Ottoman Empire

Black curtains were generally installed to get highquality photos with better lighting. The cameras were not merely used to take headshots, though. Families dressed in their best attire would go to photo studios on special occasions, taking photos in front of scenic views or black backgrounds on which "İstanbul Hatırası" (An Istanbul Souvenir) was written. Newly married couples, close friends and children used to head toward Istanbul's most famous photo studios, to pose for the cameras while looking out to the horizon. Street photographers gained popularity after the World War I.

They were addressed with humorous nicknames such as "alaminut", "dakikalık" or "şipşak", which all mean "fast" or "rapid" in Turkish. Indeed, the word "alaminut" derives its origin from a French culinary term "à la minute" literally meaning "in a minute." Such photographers were mainly working near public institutions. Ottoman street photographers used to have black backgrounds in different shapes. There were pillars, vases with flowers, birds, or flags drawn on them. Other backgrounds feature the Galata Tower, mosques, mansions, palaces, the Maiden Tower with charming embroiders.

Soldiers used to take photos in front of another background inscribed with "Askerlik Hatırası" (A military memory). Young soldiers then sent the photographs to their families or beloved. Following the arrival of cameras, their bellows were mostly imported from Europe and the boxes were made in Istanbul. Photographers spent hours in darkrooms getting their photograph processed. Many photographers were requested to take photos in which people's face looked clear. If there were any shadows, it was the photographer's fault.

Interestingly enough, the Ottoman-era photo studios resembled workshops. You could find wardrobes with a variety of clothing, mirrors and combs. While there were scarves for women, men would find a "fez," a felt hat with tassel on the top. The studios were full of books, inkpots, and the traditional "zeibek" clothes. The zeibeks are known as the soldiers from the Aegean Region of Anatolia.

Furthermore, the photographers used to arrange everything. If someone was frowning, then the photographer calmed him down. They could make people smile or tell you how to sit down while taking photos. This is why photographs from the past look, to modern eyes, as though those posing are more robot-like than human. Photographs and poses were laced with meaning.

If someone was leaning with one hand on his neck, it would mean he was thinking of his lover. Such photographs would be accompanied with a special message. On the other hand, young people were taking photos while sitting and reading a book in front of a table. Some Ottoman clerks had similar photos.

At that time literacy was of significant importance and young educated men could easily find someone to marry. More explicitly, young couples would first see each other through photos. A young man's photograph was passed from hand to hand among the family members of the girl and everyone would pass their opinion as to his suitability.

While some of them do not like the man's hand, another might be mesmerized with his bloomy eyes. Afterward, the groom candidate was either accepted or rejected.

Some traditions still live on in one form or another. Like today, taking too many photographs was regarded as inappropriate, bordering on narcissism while a small, personal picture would often go a long way, although the messages of yore are perhaps a little more long winded and elaborate than the abbreviations preferred by 21st century photographers.

The autographed photos were generally sent in envelopes to relatives. Before signing and dating the photo, people used to write a moving message such as "Gûşe-i nisyânaatma sakla solgun resmimi" (Do not throw away my faded photo and keep it) or "Hatıra olmak üzere takdim ettim resmimi" (I am presenting this photo as a memory).

If the sender loves the recipient, then he would write, "Şu zavallı hayalim iltifatınıza nâil olursa, hayatımın en unutulmaz saadeti olacaktır" (If you pay a compliment to my vulnerable existence, it would be the most unforgettable happiness of my life). Lovers also described themselves with such moving phrases. If the couples did not know each other in person, then would they send photographs without an autograph.

Some photographs were specially designed by putting a woman's shadow on the top and the sender's photo at the bottom. Alternatively, the couples' headshots were displayed in two circles. Before putting the photo into an envelope, the young man drew a heart with an arrow or wrote "Ah minelaşk" (How I suffer from your love). Above all, such practices were secretly observed among the society since it was considered a taboo. At those times, there were also female photographers, exclusively taking women's photos. Women were free to wear what they want or select among many interesting costumes like navy or dancer outfits. Such photos, however, were never displayed on the shelves of studios.

Önceki Yazılar

-

RAMADAN WAS DIFFERENT IN THE ASR AL-SA‘ADAH…4.03.2026

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025