.jpg)

A FALSE MESSIAH IN ANATOLIA

Although the Ottomans called anyone who converted to Islam a muhtadi (one who has found guidance), they withheld this name from one group, referring to them instead as awdati (returnees or Dönmes). Although few in number, the Dönmes held very important positions in Ottoman social and political life and managed to maintain power for many years.

A significant Jewish community had long lived in Ottoman lands. The Ottoman government recognized them as a distinct millet (community/nation). Many of them were Jews who had fled Spanish persecution in 1492. They spoke a language called Ladino, a mix of Hebrew and Spanish. Thessaloniki, İzmir, and Istanbul were the cities where they lived in greatest numbers.

The Kingdom of God

In 1648, a rabbi named Sabbatai Zevi (or Sabetay Zwi) living in İzmir claimed to be the messiah. Indeed, Jews had long awaited a messiah to save humanity before the Day of Judgment, overthrow the ruler of the time, gather Jews in Jerusalem, and establish the “Kingdom of God.” Christianity and Islam also hold belief in a messiah, though in different forms.

However, few believed in Sabbatai Zevi. He traveled through various cities. Finally, in 1666—which he considered the beginning of the apocalypse—he declared his messiahship to everyone. He changed Jewish prayers, removed the sultan's name from prayers and inserted his own. Some began to believe he was the long-awaited savior king of the Jews. He divided the world into 38 kingdoms and appointed his loyal followers to each.

As a result, the chief rabbi in Istanbul reported him to the government. Zevi was exiled to Çanakkale. When he continued his activities, he was brought to Edirne before Sultan Mehmed IV. Fearing execution, he pretended to convert to Islam and took the name Mehmed. The Sheikh al-Islam Vani Mehmed Efendi, who was present at the time, could not help but say: “I am as sure as my name that this man has not truly become a Muslim. But alas, our religion judges by appearances.”

His followers also publicly declared that they had become Muslims. Islam judges based on appearance. Even the Prophet Muhammad did not confront those he knew to be hypocrites for this reason. Moreover, among them may have been sincere Muslims.

Sabbatai Zevi

18 Principles

Zevi, who was placed under residence in Gallipoli, did not stop his activities. He published 18 principles of the sect called Sabbateanism (Sabbateanism):

“God is one. Sabbatai Zevi is the messiah. False oaths shall not be taken. When the names of God and the Messiah are mentioned, respect shall be shown. Meetings shall be held to understand the secret of the Messiah. No one shall be killed. Adultery shall not be committed. The 16th day of Kislev (the 9th month of the Jewish calendar) shall be celebrated. False testimony shall not be given. Mutual kindness and compassion shall be shown. Psalms (hymns from the Torah) shall be read secretly every day. The customs and apparent religious practices of Muslims shall be followed. Fasting shall be observed. Sacrifices shall be offered. No marriages with Muslims shall occur. Muslim holidays shall be respected.”

Zevi was caught while conducting secret rituals with his followers. He was interrogated by Grand Vizier Fazıl Ahmed Pasha and exiled to Albania with his followers. He died there in 1675. Since the issue was resolved through exile, the government did not resort to execution. For the Ottomans, so long as the order was not threatened, no one’s belief was interfered with.

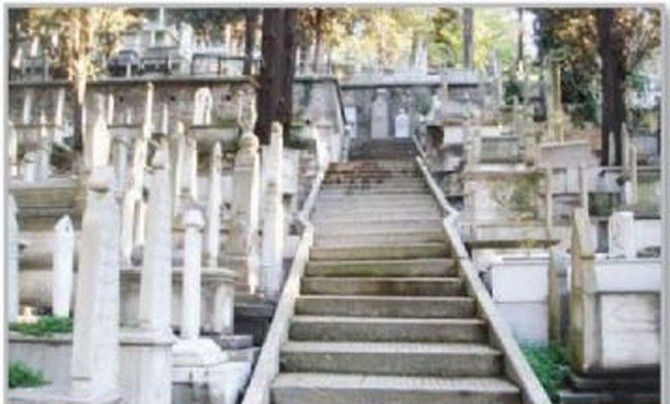

The grave of Sabbatai Zevi in Ulcinj, Montenegro

Key Points...

Sabbateans referred to themselves with names such as ma’aminim (believers), haberim (associates), and ba’ale milhamah (warriors). They interpreted the esoteric meaning of the Torah, and by interpreting many Jewish laws and commandments differently, followed a path similar to the Batinis in the Islamic world. They read Zevi’s commentary on the Torah called Zohar (Light).

A hundred years after Zevi's death, they split into three groups. Those who considered Zevi’s brother-in-law Yakub Qerido as the next messiah were called Yakubis. Another group believed that Osman Baruhya Ruso carried the soul of Sabbatai Zevi; a different group rejected this. The first were called Karakaşlar, and the second group that continued Zevi’s tradition were called Kapancılar.

They lived separately. They did not marry among each other or with outsiders. Even their cemeteries were separate. Üsküdar’s Bülbülderesi and Karacaahmed (8th section) cemeteries belonged to the Karakaş and Kapan communities; Feriköy was for the Yakubis. The Bülbülderesi cemetery was divided into Karakaş and Kapan sections. After 1960, Muslims also began to be buried there. The Kapan cemetery was used until 1935. The Karakaş section is still active and well-maintained. The Karakaş community buried multiple deceased in a single grave. The Kapan section is neglected. They now also bury in Zincirlikuyu. Yakubis bury in Feriköy. Tombstones bear images and symbols.

Even the Jewish community, considering Sabbateans heretical, excluded them. For many years they lived as apparent Muslims while practicing their beliefs and worship privately in their homes. Among them were Bektashi, Mevlevi, and Melami sheikhs, and even a Sheikh al-Islam (Hayatizade Emin Efendi – 1748). The poet Esat Dede (d. 1911), the head of the Kasımpaşa Mevlevi lodge, was one.

Even the cemeteries of the followers of Sabbatai Zevi, who split into three groups, are different

Sütçü Baba

The most important day for the Dönmes is the Kuzu Festival on 21 Azar (March), commemorating Prophet Abraham’s sacrifice of his son. A lamb feast is held. There are rumors that, in the past, wife-swapping occurred. Some Dönme even believe that the 1917 Great Fire of Thessaloniki was divine punishment for this.

They refer to Sevi as “Sütçü Baba” (Milkman Father) to avoid mentioning his name; offerings of milk and honey are made for him. In the evenings, a candle is lit in front of the house to show signs of life inside. A guest room is always kept ready for the messiah. At gatherings, an empty chair is left.

Circumcision is performed not at 7 days old but later in life, like Muslims. Ladino prayers are recited at funerals. Community aid money is collected under the name “Sorma ver” (Don’t ask, just give).

On July 24th, they celebrate a single Sabbath which they say substitutes for all Sabbaths of the year. They eat pork because Sevi was antinomian—that is, as he is accepted as the messiah, he can alter or abolish religious rules.

Religious instruction is conducted by volunteer rabbis within the community. The society has both religious and secular leaders. They gather in community houses, where young people meet and marry.

To preserve the culture, wealth, and secrets, endogamy is practiced. They do not even marry other Dönme groups. Anyone who marries an outsider is ostracized—but not excommunicated. Calendars are shared, alms are accepted, and funeral services are provided. However, the person is not admitted into the community and must perform rituals alone.

Community children do not know they are Dönme; they learn by coincidence, as their parents do not tell them to protect them. This reflects Sevi’s command to remain silent. Some see this secret as a curse and hide it for that reason. They prefer to be called “Selanikli” (Thessalonian). In the past, everyone spoke Ladino within their families.

Especially since Sevi, almost every Dönme family has kept a genealogical tree. Everyone has one public and one secret name. The secrecy stems from the fear that knowing both names could allow for sorcery. Everyone is known to have a Spanish-origin surname, but it is not used.

The Status Quo and the Dönme

The Dönme have always been a closed group living a European lifestyle, in contact with Europe, financially well-off or wealthy, educated, and multilingual. They believe they are different and superior, that God loves and protects them the most.

They became the recruits of the Republic. They were familiar with the West and lived in a Western manner. They are distant from the rituals of both religions. A few pray or fast and are sincere Muslims. Very few follow Sevi’s rituals.

In the Dönme neighborhood of Thessaloniki where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk is said to have been born, there is the Yeni Cami (New Mosque), built by the Dönme in 1902. Atatürk’s father, Ali Rıza Bey, is buried in this mosque’s courtyard. It is said that the houses in this neighborhood were connected from below, allowing people to move between them as if entering their own homes—thus enabling secret worship away from prying eyes.

From the 1880s onward, ethnic identity began to surpass religious identity. After World War II, intermarriage increased. Today, most describe themselves as distant from religion and faith. Almost all consider themselves ethnically Jewish. Some have no interest in these matters. Very few are connected to memories, traditions, and rituals. Today, the Dönme population is estimated at around 40,000 people, with about 5% said to follow religious rituals.

Food culture is very much alive among the Dönme. It is nearly the only continuing ritual of the community. Anyone who makes “mafiş” dessert, snow-white meatballs, or cracked-wheat dolma is a Dönme. Their cuisine also includes roasted chestnuts, leek meatballs, and eggplant börek.

Önceki Yazılar

-

RAMADAN WAS DIFFERENT IN THE ASR AL-SA‘ADAH…4.03.2026

-

“FASTING WAS MADE OBLIGATORY ALSO UPON THOSE BEFORE YOU”25.02.2026

-

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE?18.02.2026

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025