.jpg)

GREETINGS TO YOU, O OTTOMAN SANJAK!…

Everything left from the Ottomans was changed in Turkey. Even the schools, faculties, institutions, and cities they had established were given other names. From the university to the courts, from the population registry to the air forces, from the National Assembly to the Council of State, everything that functions properly in Türkiye today was founded during Ottoman times.

What was newly established were things that did not exist in the world at that time anyway. For some reason, their crescent-and-star flag was not touched. That was a good thing. In the first years of the Republic, a blue flag was considered instead, but perhaps due to concerns of its resemblance to the Greek flag, it was abandoned.

Its Size and Ornament Inspire Fear

Among the flags of the world, there seems to be none as deeply meaningful as the crescent-and-star. For centuries it adorned the dreams of enslaved Muslims; the famous Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyli expressed this in his song (The Black Sea was struggling, at the Turkish flag looking).

For the Tatars of Poland, today their only remaining bond with Islam is almost nothing but the crescent-and-stars on their tombstones.

In time, Muslim countries that gained independence always preferred to let the crescent-and-star wave in their skies. Here are Tunisia, Algeria, Pakistan, East Turkestan, Singapore, Malaysia…

Reciting the Friday sermon (khutbah) in the name of the sultan and minting coinage, as well as the tabl (mehter, Ottoman military band), banner (sanjak), and tugh (horse-tail standard), were symbols of sovereignty in the Ottomans.

Raise the Tughs

The tugh, consisting of a horse’s tail attached to a spear, was a symbol of sovereignty coming from the ancient Turks. Behind the sultan, 7 or 9 tughs would be carried. Viziers also had tughs. The flag is a symbol of a nation’s existence, a memory of its history. Its value does not depend on whether it is made of cotton, satin, or silk. The flag represents the sovereignty and honor of the state. For this reason, it is shown respect.

Ottoman vizier and historian Cevdet Pasha says: “The secret and wisdom in the use of the flag is this: when a group gathered for a certain cause comes together under a flag, unity is brought about among them. The flag is the means and symbol of them becoming of one heart and one tongue. By gathering under it, they imagine themselves as one body, and they become more closely connected with each other than with their relatives. As long as the flag remains standing during battle, it means they are ready and capable of fighting. They do not lose hope of victory. Those whose flag is captured and destroyed fall into fear and disperse. The size and ornamentation of flags also frighten and terrify enemies. Just as the sound of the band gives zeal and bravery to the soul through the ear, the appearance of flags to the eye gives determination and instills fear in the enemy.”

Flag and Sanjak

The Turkish word bayrak (flag) derives from the Ottoman Turkish word batrak (from the Old Turkic root bat- ‘to thrust, to stick into’ + the suffix -rak), meaning a staff or standard planted into the ground. The word sanjak comes from the Turkish word sançmak (to thrust, to stab), because its tip, like a spear, was thrust into the enemy. Both are used interchangeably.

Each military unit or statesman could have a sanjak. But generally, the flag was only one. Its Arabic equivalents are rayah, ʿalam, and liwa. The liwa was wrapped around a spear and marked the position of the army commander. The rayah given to each unit was tied to the tip of a spear so that it would wave in the wind.

In the first year of the Hijra, the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) himself tied a piece of white cloth to the tip of a spear for a 30-man force under the command of Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib, sent against the Quraysh caravan returning from Syria, and placed it in the hand of Abu Mursid.

This liwa al-bayda was the first flag of the Muslims. The Prophet used two kinds of flags in battles. His rayah was black. His liwa called al-‘Uqab was smaller and white. One of these banners, which passed to the Ottomans during the reign of Sultan Selim I, was preserved with respect and care (this is the liwa al-sharif). The Abbasid flag was black.

The Double-Headed Eagle

There are some accounts about the flags used by some of the Turkish states before the Ottoman Empire. The Göktürks used a sky-blue banner with a wolf’s head, the Kyrgyz a red and green one, the Huns a yellow one with a dragon image, the European Huns a white one with a bird image, and the Hephthalites (White Huns) a white one with three stars. Among the first Muslim Turkish states, the Ghaznavids used a green banner with a white crescent and a huma bird image. They also had a special black state flag. The Karakhanid banner was orange, with an image of nine tughs upon it.

The Khwarazmshahs used black, the Mughals red-yellow. On Timur’s banner there was a blue field with three full moons arranged in a triangle. The Golden Horde banner was a white field with a red crescent facing upward. The Seljuk banner had a blue field with a white double-headed eagle and depictions of a taut bow and arrows with black stripes. Later they used a black flag.

The Legend of the Crescent and the Star

In the Ottomans, in the place where the sultan was present, a red banner would be unfurled representing the dynasty, and a white banner representing the state. The banner sent by the Seljuk sultan to Osman Ghazi was white.

In later centuries, beginning with Sultan Selim III (1793), the two were combined, and the official flag became a red field with a white crescent and star. The eight-pointed star was changed to a five-pointed star during the reign of Sultan Abdulmejid (1842).

The story that it was born from the reflection of the moon and stars in the sky upon blood spilled in a battle is a legend. The crescent on the flag has a very old history. The Prophet Muhammad gave Sa‘d ibn Malik a black banner with a white crescent upon it. Crescents can also be found on the flags of the Ghaznavids, Golden Horde, Fatimids, Ayyubids, Mamluks, and Anatolian beyliks.

Before the Ottomans crossed into Rumelia, the symbol of Illyria was also a red field with a crescent and star. Perhaps the reason why the founders of Turkish Republic did not object to the crescent-and-star flag was that for many of them this symbol reminded them of their homeland.

Some sources say that the chancellor of King Richard the Lionheart of England, William de Longchamp, bore a coat of arms with a crescent and star; and that during the Third Crusade, when the King passed through Cyprus in 1191, he saw here a coat of arms consisting of a crescent and eight stars and liked it.

At the tops of flags there were metallic crescents as finials ('alam). On some Göktürk coins, too, crescent-and-star symbols are found. According to one narration, Seljuk flags had a crescent-shaped ornament at their tips; in fact, the flag sent by the Seljuk sultan to Osman Ghazi also had one at its top. Since this flag was regarded as a symbol of independence, later Ottoman banners also tended towards including the crescent motif.

In the book Tsarsky Titulyarnik (Tsar’s Book of Titles), which showed high ranks and was presented in 1672 to the Tsar of Russia of that time, the crescent-and-star is shown as the emblem of Sultan Mehmed IV. Thus, the crescent-and-star’s symbolization of the Ottomans dates to before the 18th century.

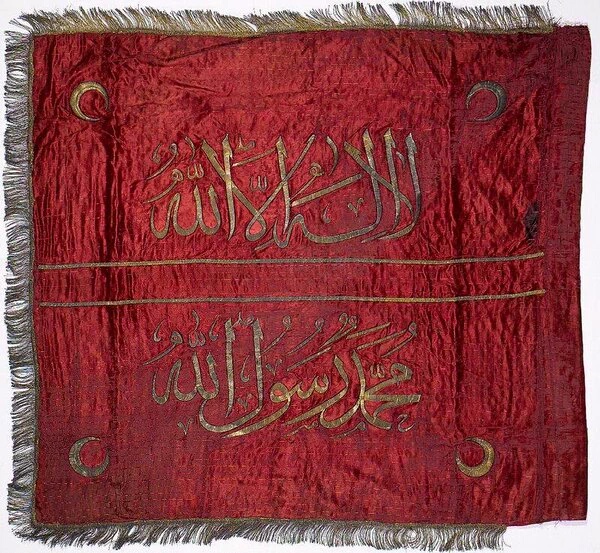

In Turkish-Islamic culture it was believed that, both because of similarity in writing and in form, the crescent symbolized Allah, and the five-pointed star symbolized the name Muhammad, which in Arabic is written with five points. The green flag with three crescents was the naval flag and represented Ottoman rule over three continents. Red regimental banners with golden fringes, embroidered with the kalima al-tawhid (There is none worthy of worship except Allah and Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah), were used until the Second Constitutional Era.

In earlier times, the Sultanate of Aceh, the Nizamate of Hyderabad, the Khanate of Khiva, the Khanate of Kokand, the Emirate of Kashgar, the Emirate of Bukhara, the Republic of East Turkestan, and the Government of the South Caucasus are known to have used crescent-and-star flags. In the Muslim world, countries that gained independence from colonialists—Pakistan, the Comoros, Malaysia, Singapore, Mauritania, Libya, Algeria, Tunisia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Northern Cyprus, among others—have also adopted crescent-and-star flags in various colors.

Önceki Yazılar

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025