.jpeg)

IT HAS BEEN MORE THAN 100 YEARS SINCE ITS ABOLITION, BUT... IS THE CALIPHATE BEING REESTABLISHED?

March 3, 1924, is the day when the caliphate, the oldest (1302-year-old) institution of Muslims, was buried in history. Now, changing circumstances and needs have brought up the subject of reviving the caliphate. Newspapers consider this a certainty. They are even suggesting candidates. But what, where, how, and who?

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) established an Islamic state in Medina in 622 after his migration and became its leader. When he passed away ten years later, the one chosen as his successor, Abu Bakr, was called the Caliph of the Messenger of Allah.

"Caliph" means successor. From then on, the leader of the Islamic state, whether he came to power through election, appointment, or force, was called the caliph as long as he met the necessary conditions for the position.

Caliphate Diplomacy

As the borders expanded, different caliphs appeared in various regions in the 10th century. When the Islamic Empire fragmented, each province had its own ruler. However, all of them, at least symbolically, recognized the caliph in Baghdad. The caliph was similar to an emperor in European history, while sultans held a status similar to kings and princes formally subordinate to the emperor.

When Baghdad fell to the Mongols, the Abbasid Caliphate continued in Cairo. In reality, governance was exercised by sultans who were nominally subordinate to the caliph. The caliph became a spiritual figure reminding Muslims of the glorious unity of the past.

According to widespread belief, after Sultan Selim I’s conquest, the Abbasid caliph in Cairo was brought to Istanbul and transferred the caliphate to the sultan. Thus, the titles of sultan and caliph merged in the Ottoman ruler. Five centuries later, the caliphate once again gained temporal authority.

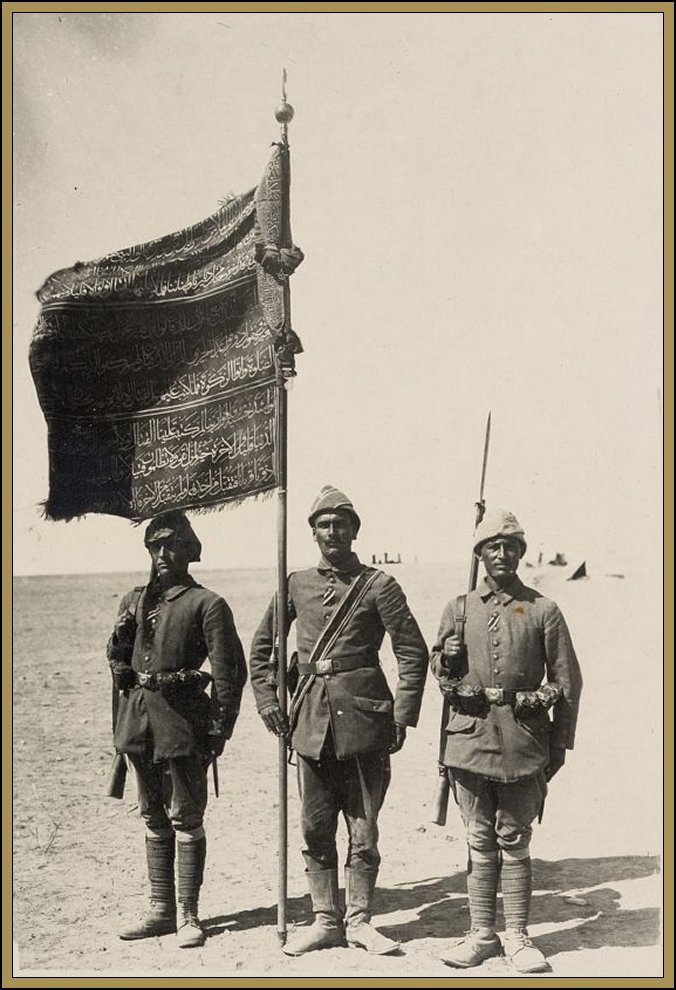

In 1535, the Shaybanid Khanate of Turkistan, in 1727, Iran, the Gujarat Sultanate, the Mughal Empire in India starting from Humayun Shah, and the Kashgar Khanate recognized the Ottoman sultan as the caliph. Requests for assistance from the Ottoman sultan, in his capacity as caliph, were fulfilled—whether from the Hijaz and Aceh against the Portuguese or from the khans of Turkistan against the Russians occupying the Volga basin.

In the Sharafnama (History of Kurds), written by Sheref Khan, one of the lords of Kurdistan, Sultan Selim I is explicitly referred to as a caliph. Sultan Suleiman I used this title in a letter to the Sharif of Mecca. The Mughal Emperor Humayun Shah referred to Suleiman as “evreng-i khilafat” (the throne of khilafat) and “hafiz-i shar‘-i mubin” (protector of Islamic law) in his correspondence.

In the inscription of the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, the phrase “hallada khilafatahu khuludu’z-zaman” appears, meaning, “May Allah make his caliphate eternal!” The Ottoman historian Şerifi referred to Sultan Selim II as a caliph in the Fetihname-i Kıbrıs (The Cyprus Deed of Conquest). All of this demonstrates that the Ottoman sultans used the title of caliph from the beginning and attached great importance to it.

However, the special emphasis placed on the caliphal title by later Ottoman sultans can be attributed to historical circumstances. They understood that it was not a separate title from state leadership, as Islam does not have a clerical hierarchy.

In 1774, Crimea was lost. From then on, the sultan claimed spiritual authority over the Muslims in the lost territories to protect their religious and worldly interests, and he gained recognition for this claim among world powers. Until that time, the sultan’s authority was limited to his own territories, but with the caliphate, he attained a position akin to that of the Pope over the world’s Catholics.

The Quranic verse “Obey those in authority among you” and the hadith stating that “whoever dies without pledging allegiance to a leader dies the death of jahiliyya (the age of ignorance, without spiritual guidance in the pre-Islamic period)”, as well as the prohibition against living in a land without a sultan, necessitated allegiance to a caliph who acted in accordance with Islamic scholars. This principle provided the Ottoman sultans with a legitimate foundation for their spiritual authority over Muslims living outside their dominions.

A Hope in Istanbul!

The emphasis that Ottoman sultans placed on their caliphal status in international affairs does not mean that they were not considered caliphs before or that the caliphate was merely a spiritual position. The Ottomans’ actions were driven by pragmatic and diplomatic considerations.

Sultan Abdulhamid II, in particular, highlighted this title as part of his policy of Islamic unity. In territories under non-Muslim rule—Russia, Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Greece—muftis and judges appointed from Istanbul continued to function as representatives of the caliph. This tradition, albeit weakened, has persisted to the present day.

The impact of this policy was seen in the early 20th century. Muslims worldwide, who had fallen under colonial rule, always looked to the caliph in Istanbul as a source of hope. They provided incredible material and moral support during the occupation of Anatolia, as Islamic law dictates that it is an obligation for Muslims to rescue the caliph from enemy captivity.

Britain, which ruled over a quarter of the world and had a significant Muslim population, feared this influence and, in the 19th century, focused its policies on diminishing and eventually abolishing the caliphate. Its refusal to aid the Ottomans in the Russo-Turkish War (the War of '93) and the Balkan Wars, its involvement in the deposition of Sultan Abdulhamid II, and even its role in dragging the Ottomans into World War I were all part of this strategy. During the Greco-Turkish War, Britain refrained from supporting either Ankara or Greece—if Greece won, the caliph would be their captive; if Ankara won, they could infiltrate it more easily.

After 1909, the Second Constitutional Era curtailed the temporal authority of the caliph On November 1, 1922, the sultanate was abolished. A purely symbolic caliphate with no executive power was established. Instead of Sultan Mehmed VI, the heir apparent, Abdulmejid II, was appointed to this position by the Ankara-based National Assembly. Sultan Mehmed VI, in a declaration from San Remo, asserted that this constitutional amendment was illegitimate, as it had not received the sultan’s approval. He also claimed that separating the sultanate from the caliphate was religiously and legally impossible.

Önceki Yazılar

-

WOMAN IN THE EASTERN WORLD11.02.2026

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025