.jpg)

WHAT WAS THE LAW OF THE OTTOMAN STATE?

In the nineteenth century, the movement of codification in Europe gained momentum. States enacted civil codes. They also began to exert pressure on the Ottoman government, saying, “Let us know what your law is.” Did the Ottoman State have no law until that time?

The basis of Ottoman law is shar‘i law (Islamic law derived from the Qur’an and the Sunnah). The provisions of this law were not determined by laws enacted by authorized authorities, as in other legal systems. Scholars determine shar‘i law through their own ijtihad (legal interpretation) by interpreting the Qur’an al-Karim and the hadith al-sharif. Therefore, the fiqh books they wrote are law. If every sentence of these books were numbered, they would almost resemble today’s laws. For this reason, in Islamic states there was no need for legal texts in the modern sense.

Whatever the Ruler Commands…

If every scholar wrote books according to his own ijtihad or madhhab (school of thought), which of these would be applied as law? Each qadi (judge) applies his own madhhab in court. The madhhab of the parties is not taken into consideration. However, if the ruler orders the application of a specific madhhab, judgment is rendered accordingly, regardless of the qadi’s own madhhab. In matters disputed among fuqaha (scholars of Islamic law), it is possible for the ruler to turn the opinion he prefers into law.

There have been attempts at this in history. For example, the Abbasid caliph al-Mu‘tadid, in 896, promulgated an imperial decree in accordance with the Hanafi opinion that when the only heirs are dhawi al-arham (relatives connected to the deceased through a female intermediary), they inherit the estate. Until then, the Shafi‘i opinion—according to which dhawi al-arham could not inherit and the estate reverted to the state treasury—had been applied.

The Seljuk Sultan Malikshah, in 1092, codified some disputed provisions of Islamic private law, with the assistance of the famous fuqaha of the time, under the title Masa’il-i Malikshahi fi al-Qawa‘id al-Shar‘iyya, and ordered its application throughout the Seljuk realm. During the Seljuk period, there were qadis in every city who ruled according to Islamic law. However, in accordance with the tradition inherited from the Uyghurs, the Seljuks applied old Turkish traditions in matters whose regulation was left to the ruler by Islamic law. This gave rise to ‘urfi law (sultanic law based on state practice), alongside shar‘i law and without contradicting it.

This tradition continued among the Ottomans as well. In the Ottoman State, ‘urfi law consisted of the sultan’s qanunnames (sultanic legal code). These were prepared in the Divan-i Humayun (Imperial Council); after obtaining the fatwa (religious ruling) of the sheikh al-Islam to ensure that they did not contradict shar‘i law, they were promulgated. Ottoman law consisted of approximately 80 percent shar‘i provisions and 20 percent ‘urfi provisions.

Unity of Law

From the sixteenth century onward, a condition was included in the appointment warrants of qadis requiring them to judge according to the most sound opinions of the Hanafi madhhab. Thus, the Hanafi madhhab became the official madhhab of the state, and Hanafi fiqh books took the place of law. In this way, legal unity in the country was ensured.

In Arab lands where non-Hanafis also lived, if a case concerned family law, the qadi would appoint a na’ib (deputy) from the parties’ madhhab and would ratify the judgment given by the na’ib according to his own madhhab. Sheikh al-Islam Ebussuud Efendi compiled his fatwas concerning some disputed issues of Islamic law and presented them to Sultan Suleiman I under the title Ma‘ruzat. After being attached to a sultanic decree, these were promulgated as law.

The practice of sheikh al-Islams presenting fatwas to the sultan on various subjects in accordance with the conditions of the time and the needs of the people, and having them proclaimed as law, continued until the end of the state. Such a fatwa could be a weak opinion of the Hanafi madhhab or could belong to another madhhab. Here, no provision that had never existed in shar‘i law was introduced by sultanic decree; rather, one of the existing provisions was put into effect. The sultan’s authority in legislation was very limited. For example, in the Hanafi madhhab, a girl who has reached puberty may marry of her own will. However, according to Imam Muhammad of this madhhab, the permission of her guardian is required. Due to the increase in abductions of girls, the opinion requiring the guardian’s consent was codified in the sixteenth century.

“It shall be done as required”

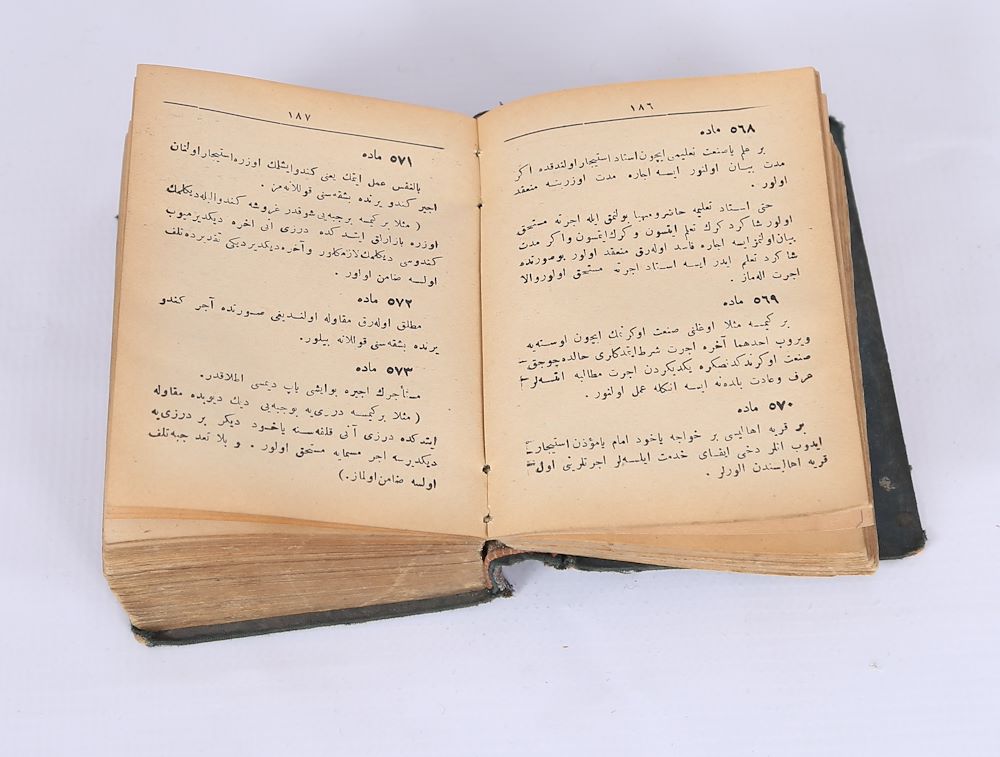

Multeqa al-Abhur, written by Halabi Ibrahim Efendi (d. 1594), who served as imam-khatib at the Fatih Mosque and as a mudarris (religious teacher) at the Sa‘di Chelebi dar al-qurra [a madrasa where huffaz (plural of hafiz, Qur’an memorizer) were trained], systematically presenting the most authoritative opinions of the Hanafi madhhab, functioned in Ottoman courts as the equivalent of civil, family, inheritance, obligations, tax, procedural, and criminal laws. This work was translated into Turkish during the reign of Sultan Ibrahim under the title Mawqufaat. The French diplomat d’Ohsson and others presented it as the Ottoman law and translated it into foreign languages. The saying, “The sultan rules the Turks, and Mawqufaat rules the sultan,” became famous.

In the nineteenth century, the movement of codification in Europe gained momentum. States enacted civil codes. Pressure began to be exerted on the Ottoman government to prepare a civil code as well. Thereupon, during the reign of Sultan Abdulaziz, a committee of scholars under the chairmanship of Ahmed Cevdet Pasha prepared the famous Majalla. After it was presented to Sultan Abdulaziz and his decree of “It shall be done as required was obtained, it was promulgated. The Majalla is a perfect Ottoman civil code. It is also the first example of a broad area of Islamic law being collectively codified in a modern manner. Thereafter, Muslim states that separated from the Ottoman State continued this tradition when making laws. Fields such as family law, which the Majalla did not regulate, continued, as before, to be filled by Mevkufat.

An Initiative from India as Well

Attempts to compile fiqh principles like a code are also encountered in Muslim Turkish states in India. However, these were not as successful as in the Ottoman State. During the Tughluqshah period, the jurist 'Aalim bin 'Ala Indarpati (d. 1384), upon the instruction of Amir Tatarhan, one of the nobles of Firuz Shah’s court, wrote the work known as Fatawa Tatarkhania. Among the rulers of the Gurganiya realm, Shah Aurangzeb Alamgir (1658–1706) saw the difficulty of benefiting from the Hanafi sources in force in the country. He formed a committee so that the most authoritative rulings in these sources could be compiled into a book in a manner understandable to everyone.

This committee, under the chairmanship of Sheikh Nizam, prepared the six-volume Al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya (Al-Fatawa al-Alamgiriya). Although this work—prepared by surveying thousands of volumes in the shah’s library and spending two hundred thousand silver rupees—did not become law because it was not promulgated by an imperial decree, it served for centuries both as a handbook for jurists in India and as a highly esteemed work in the Islamic world. These are important in that they demonstrate, on the one hand, the state’s interest in and contribution to codifying fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), and on the other hand, the manifestation of the Turk-Mongol legal tradition.

Önceki Yazılar

-

THE OTTOMAN DYNASTY OWES ITS LIFE TO A WOMAN4.02.2026

-

THE WATER OF IMMORTALITY IN THE “LAND OF DARKNESS”28.01.2026

-

THE WORLD LEARNED WHAT FORBEARANCE IS FROM SULTAN MEHMED II21.01.2026

-

THE RUSH FOR GOLD14.01.2026

-

TRACES OF ISLAM IN CONSTANTINOPOLIS7.01.2026

-

WHO CAN FORGIVE THE KILLER?31.12.2025

-

WHEN WAS PROPHET ISA (JESUS) BORN?24.12.2025

-

IF SULTAN MEHMED II HE HAD CONQUERED ROME…17.12.2025

-

VIENNA NEVER FORGOT THE TURKS10.12.2025

-

THE FIRST UNIVERSITY IN THE WORLD WAS FOUNDED BY MUSLIMS3.12.2025