.jpg)

SHEIKH ABDUH AND EGYPT ON THE WAY TO RESEMBLE EUROPE

In the Islamic world, modernist ideas first moved into Egypt, an ancient scientific and cultural center. After Muhammad Ali Pasha, who was a pious person, the subsequent governors remained indifferent to this trend or could not stop it. Egypt, which had been a privileged state since 1805, was occupied by the British in 1882 due to the unpaid foreign debts and due to its excessive expenditures, especially the Suez Canal.

A Political Quagmire

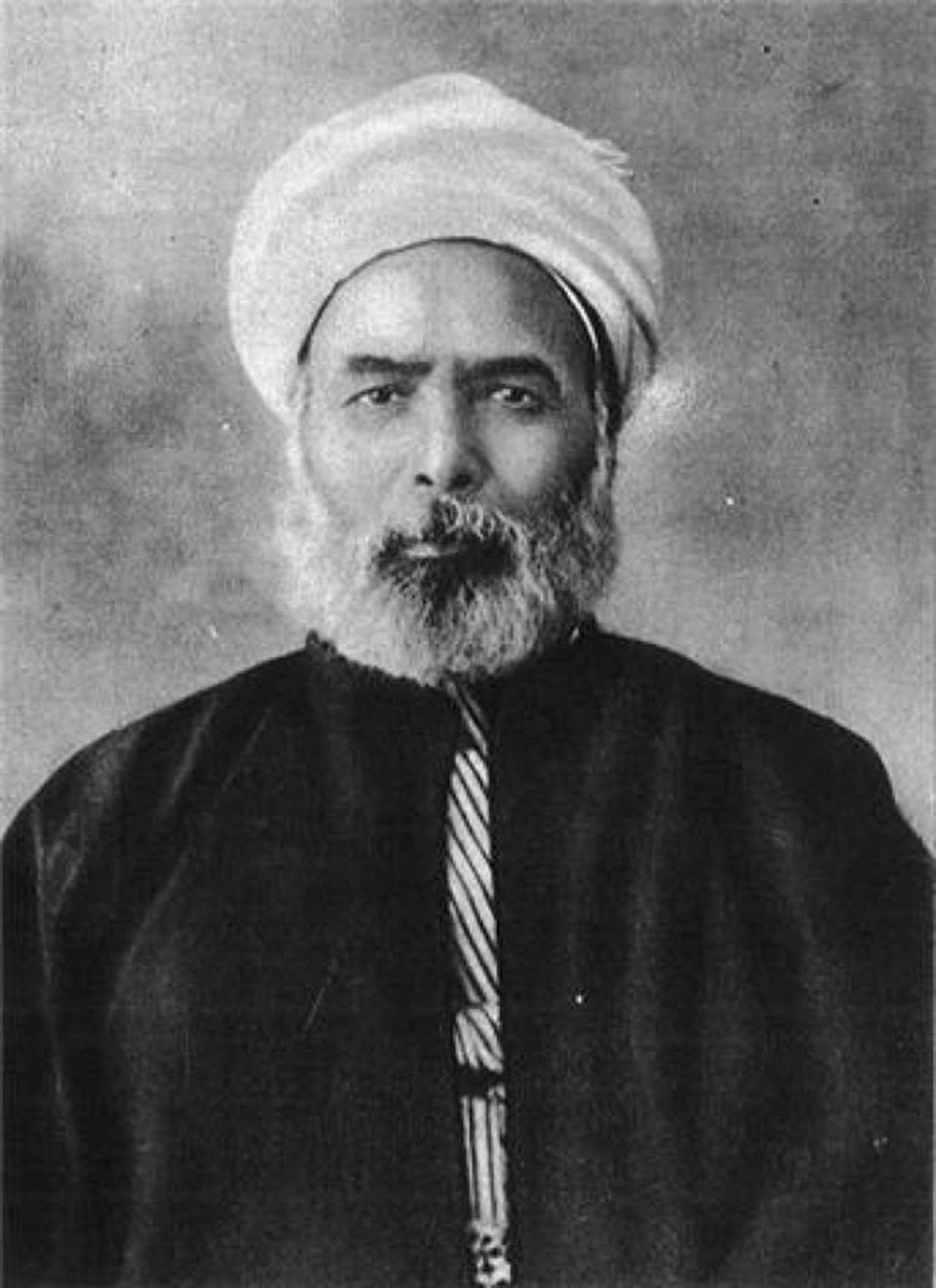

Born in Shubra in western Egypt in 1849, Sheikh Muhammad Abduh was a peasant boy. He was educated at the Madrasa Ahmadiyya in Tanta. Since he was not successful at first, he was discouraged and left his education. At the insistence of his father, he resumed his education. He was guided towards philosophy by Sheikh Hasan Tawil. Abduh was greatly influenced by the poet and the musician Besyuni.

He became a teacher after completing his education. He defended the Mu'tazila maddhab (a heretical sect in Islam) in his lectures. He worked as a writer in the newspaper al-Waqayi al-Masriyya. His meeting with Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, who came to Egypt in 1871, changed his life. He became interested in politics. He graduated from Al-Azhar University with average grades in 1877.

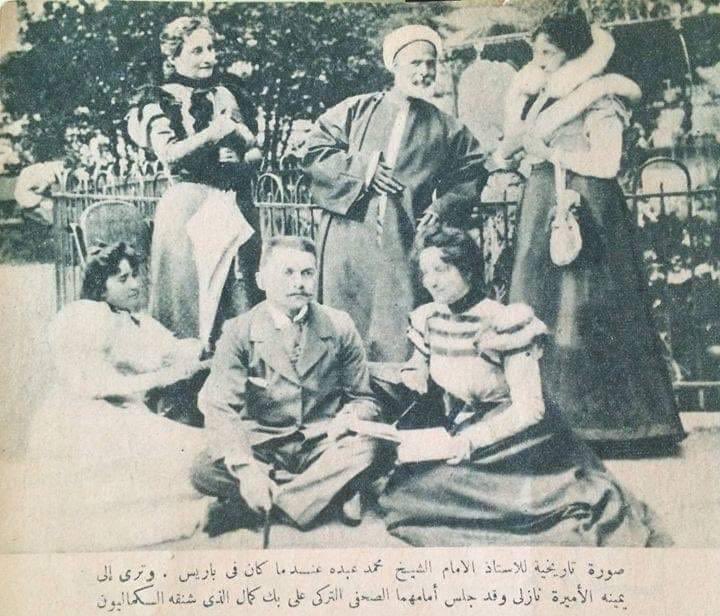

He supported the Arab nationalist Ahmed Urabi, who ostensibly revolted against the British but only served to establish British rule in Egypt. He issued a fatwa for the dismissal of Khedive Tewfik Pasha. For this reason, Abduh was exiled to Syria in 1881. He went from Syria to Paris. Here he met with orientalists. He traveled back and forth between Paris and London. Thus, he himself added three more years to his three-year exile.

Abduh published the journal Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa together with his master al-Afghani. They sent the journal, which they published against the Ottoman caliphate, to Islamic countries by using the French diplomatic mail service. The journal was suspended after 10 months. When Riyad Pasha, one of the pioneers of Egyptian modernization, came to power, he made a request to the British controller-general in Egypt, The Earl of Cromer, who then smoothed the way and allowed Abduh to return to Egypt.

Interreligious Dialogue

Abduh arrived in Beirut first. Here he lectured and wrote articles on interreligious dialogue. In 1889, he returned to Egypt. Now everything was in the hands of the British, but Abduh was well received as if he had not worked against the British. He was appointed qadi (a Muslim judge), then undersecretary of the court of appeal, and finally the mufti (a Muslim legal expert) of Egypt in 1899.

His admirers regarded him as a symbol of high knowledge and wisdom that Egypt had brought forth in the last century. They accepted him as a mujaddid (the one who restores Islam to its original purity) or even a mujtahid (an authoritative interpreter of the religious law of Islam). Combined with his intelligence and skill in using Arabic, his writings dazzled his followers.

Abduh learned French after the age of 40. He translated and published many works on philosophy in newspapers. He became head of the Cairo Masonic Lodge upon the death of his master. Therefore, the number of those who opposed him increased. His followers try to justify this either as a service to religion or because the true identity of the Freemasons was not known at that time. It is a fact that both sides used each other skilfully for their own opportunities.

The Khedive of Egypt was uncomfortable with the reformist activities of Abduh. For this reason, Abduh left Al-Azhar University. He died in Alexandria. His body was brought to Cairo with great commotion and buried there.

Aql or Naql?

Like Ibn Taymiyyah, Abduh would fight against the things he considered bid'ah (innovation) by opposing the people. Abduh, like the philosophers, was against the invalidity of continuous succession of universe (tasalsul al-hawadith). However, according to Islamic belief, if the infinite continuity of causes were not invalid, there would be no evidence to prove the existence of Allah. [If Allah were not pre-eternal, there would have been a creator of Him. Thus, the creators who were not pre-eternal would become a continuous succession, a chain. This is unacceptable.]

He collected his unique views under the name of Risalat al-Tawhid and this work was published two years after his death. He believed that if aql (reasoning) and nass (explicit statement within the Quran or hadith upon which a ruling is based) conflict, aql would be preferred by neglecting nass. Therefore, he did not accept miracles. His purpose was to make Islam appear more pleasant to Europeans.

For example, he interpreted the Ababil birds mentioned in the Surah Al-Fil as mosquitoes and the stones thrown as microbes. According to Abduh, the throne of Bilqis (Queen of Sheba) was not brought to the Prophet Solomon in an instant, on the contrary, another similar throne was made. Abduh believed that a prophet was only an ordinary person who was recognized as honest and that the Prophet Moses splitting the sea with his staff was nothing but a natural phenomenon of changing tides.

His permission for drawing of living things, sculpture, insurance, interest, and wearing hats caused a backlash. He was a supporter of free ijtihad (legal interpretation) and was against adherence to a single maddhab. Abduh started a new era in the Islamic world. Many educated people in various Muslim countries followed in the footsteps of Abduh, and the conservative-modernist distinction in the Islamic world became more pronounced.

The Deception of al-Ittihad al-Islamiya

Abduh believed that it was necessary to train new cadres for the realization of his ideals. For this reason, he sent reform projects filled with sycophantic expressions about education to the caliph of the time, Sultan Abdulhamid II. The Sultan, who knew al-Afghani very well, did not pay much attention to his disciple.

He put forward his ideas with the slogan of al-Ittihad al-Islamiya (Islamic Unity), that is, the gathering of the Muslims of the world under a political unity. However, this slogan deceived many people. In fact, his ideas coincided with the British imperialist policy. He became a fierce opponent of the Ottoman caliphate, especially Sultan Abdulhamid II, whom he saw as one of the biggest obstacles to carrying out his mission.

The British intelligence officer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who was the architect of the policy of overthrowing the Ottoman caliphate under the guise of Arab nationalism, was a friend of Abduh. In his letter to the Sultan, Abduh said, "The preservation of the Ottoman State is the third pillar of faith after belief in Allah and His Messenger". On the other hand, in a letter he wrote to his friend Blunt in 1882, he said that the Ottomans were cruel, that they had left only a bad legacy in Egypt and that the entire people hated them.

The appointment of Abduh as mufti of Egypt with the support of The Earl of Cromer is a major strategic victory for the Islamic modernists. During his time as a mufti, he did not miss the opportunity to intervene in Sharia courts, waqfs and madrasas.

Al-Azhar University, which had been founded by the Shia Fatimids, but had been the stronghold of Sunnism for centuries, thus lost its former scientific brilliance and prestige in the eyes of Muslims. So much so that the books used in high school and middle school began to be taught to university students as well. Even the Islamic modernist professor Muhammad Tavit al-Tanji used to say that the quality of al-Azhar had deteriorated due to the transition from the madrasa system to the European school system.

Abduh gained many supporters among foreigners thanks to his ostentatious writings. British orientalist Edward Browne on his death. Upon the death of Abduh, the British orientalist Edward Browne praised him to the skies in his condolences. In his work titled al-Mawqif, Sheikh al-Islam Sabri Efendi said, “Abduh could not bring the disbelievers even one step closer to religion, but he brought most of the students of Al-Azhar closer to being disbelievers”

During his lifetime and after his death, Abduh was criticized by many scholars, notably Yusuf al-Nabhani, a Beirut scholar, Yusuf ed-Dicvi, a professor of al-Azhar, and Sheikh al-Islam Sabri Efendi. When Sabri Efendi read about Abduh's debate with Christian journalist Farah Antun, he could not help but say "Sheikh won the fame but his opponent won the argument".

The Trivet

Al-Afghani appeared as if he had been a great reformer aiming to revive the Islamic world. However, according to some, he was a madman who thought he was the Mahdi, and according to others, he was a Shiite working for British intelligence. Sultan Abdulhamid II first considered entrusting him with the task of strengthening the Ottoman caliphate among the Shia Arabs in Iraq. However, he gave up on this idea when he got information that al-Afghani was trying to make an agreement with the British and establish an Iraqi-based Arab caliphate and had him detained in Istanbul.

In a letter from Egypt to his master in Paris, Abduh wrote, "You know us inside and out. On the surface, we are doing what the religion requires. But actually we are on your path. We will cut off the religion's head with the sword of religion". These words signaled that their mission was to obliterate the traditional religion that they found "degenerate" with an ostensibly "pure ideal religion." Taqiyya (concealing one's true belief) is one of the fundamental principles of Shi'ism.

In this task, al-Afghani undertook the plan, and Abduh the program. One attempted to convert Islam to a civil religion, the other to a political religion. Al-Afghani acted as Martin Luther. Al-Afghani-Abduh-Rashid Rida trio complemented each other like a trivet. They shaped the way of thinking of modernists in the Islamic world. The mistakes and weaknesses of al-Afghani and Abduh, who were woefully inadequate in religious sciences, were tried to be completed by Rashid Rida, who was more knowledgeable than both of them.

No one had been as useful as this trio to British politics in the region. The influence of Sheikh Abduh spanned a wide spectrum, including Musa Bigeev, Mehmed Akif Ersoy and Said Nursi. Akif, who translated Abduh’s writings into Turkish and introduced him in Turkey, described him as "Egypt's greatest master, Muhammad Abduh". "I also want a reform, but like Abduh," he said, pointing to the mission of his master.

[The endeavours of Sheikh Abduh and the adventure of modernism's entry into the Islamic world are well described in the following books: Muhammed al-Huseyn, al-Islam wa’l-Hadaraat al-Garbiyya, Beirut 1399/1979; Nikki R. Keddie, An Islamic response to Imperialism, London 1983; Elie Kedourie, Afghani and Abduh: An essay on religious unbelief and political activism in modern Islam, London 1997.]

Önceki Yazılar

-

"WOE TO THE ENEMIES OF THE REVOLUTION!" What Was The People’s Reaction To The Kemalist Revolutions?2.07.2025

-

DEATH IS CERTAIN, INHERITANCE IS LAWFUL!25.06.2025

-

THE SECRET OF THE OTTOMAN COAT OF ARMS18.06.2025

-

OMAR KHAYYAM: A POET OF WINE OR THE PRIDE OF SCIENCE?11.06.2025

-

CRYPTO JEWS IN TURKEY4.06.2025

-

A FALSE MESSIAH IN ANATOLIA28.05.2025

-

WAS SHAH ISMAIL A TURK?21.05.2025

-

THE COMMON PASSWORD OF MUSLIMS14.05.2025

-

WERE THE OTTOMANS ILLITERATE?7.05.2025

-

OTTOMAN RULE BENEFITED THE HUNGARIANS30.04.2025